Protein Distribution in Controlled Feeding Studies: Methodological Overview

Understanding the research on protein distribution, muscle protein synthesis, and amino acid metabolism requires familiarity with the sophisticated methodologies employed to measure these processes. This article provides an overview of how controlled feeding experiments investigating protein distribution are designed and conducted.

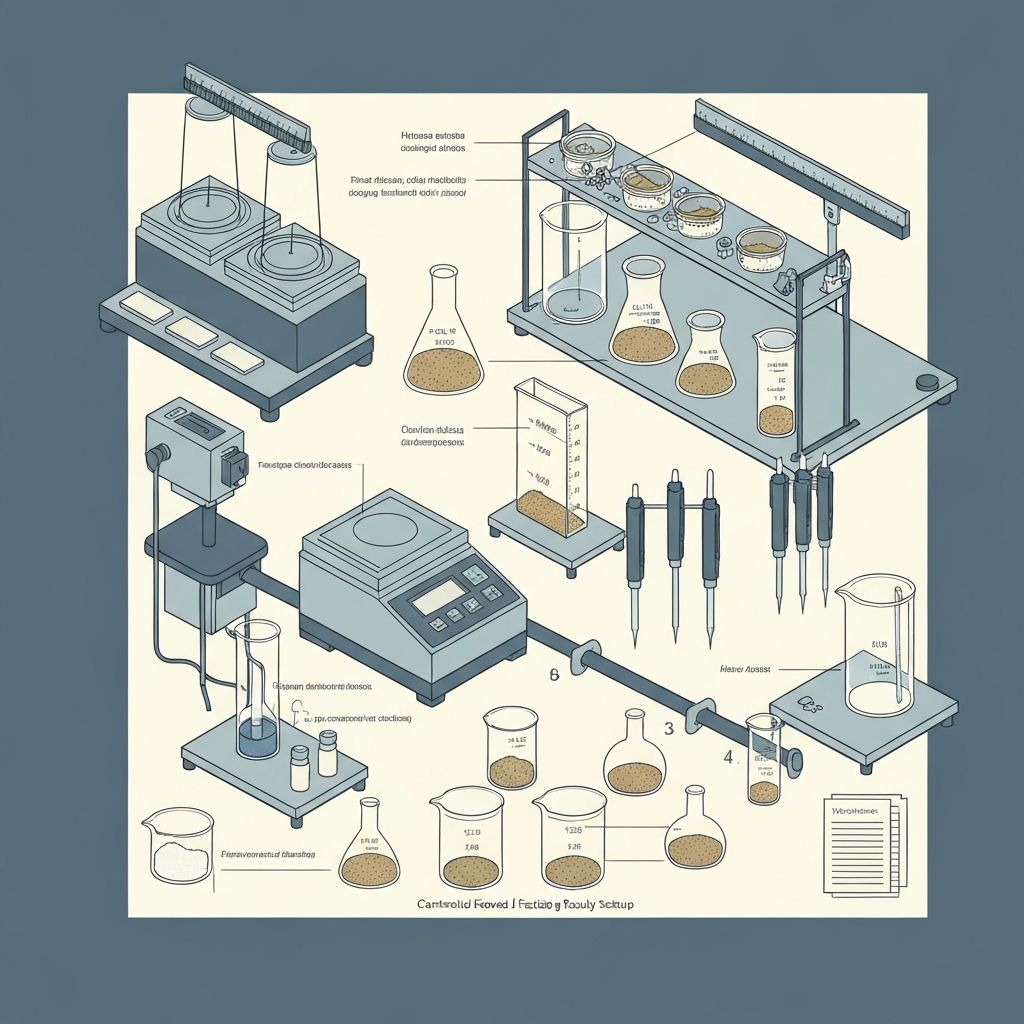

Controlled Feeding Study Principles

The gold standard for investigating protein distribution effects employs controlled feeding protocols where researchers provide all food and beverages to participants, ensuring precise control of nutrient intake. This approach eliminates variables inherent in free-living dietary assessment: self-reported intake inaccuracy, natural variation in food composition, and inconsistent eating patterns.

In controlled feeding studies, participants consume all meals at designated times under observation. Each meal's nutrient composition is carefully analyzed and recorded. Blood samples are collected at predetermined intervals to measure circulating amino acid concentrations, hormonal responses, and other biomarkers. Muscle tissue samples may be obtained via needle biopsy to directly measure muscle protein synthesis rates and related signaling molecules.

Study Duration Considerations

Controlled feeding studies examining protein distribution effects vary in duration from acute studies (single day) measuring immediate response to meals, to longer studies (7-14 days) examining adaptation to distribution patterns across multiple days. Acute studies capture the immediate metabolic response; longer studies examine whether acute responses persist or whether adaptation occurs with sustained exposure to particular distribution patterns.

Measurement of Muscle Protein Synthesis

The primary outcome in most protein distribution studies is muscle protein synthesis rate. Direct measurement employs stable isotope tracer methodology—a non-radioactive approach injecting labeled amino acids (most commonly labeled with stable carbon or nitrogen isotopes) and quantifying incorporation of these tracers into new muscle proteins. This technique permits precise measurement of synthesis rates without radiation exposure.

Stable Isotope Tracer Protocol

Participants receive an intravenous or oral bolus injection of isotopically-labeled amino acid (commonly labeled leucine or phenylalanine) at a specific time point—typically following a meal or during fasting baseline periods. Over subsequent hours, blood samples are collected to measure tracer appearance and disappearance. Muscle tissue samples (obtained via needle biopsy, typically 5-10 mL needle inserted into muscle and withdrawn with tissue) are analyzed for tracer incorporation into protein. The rate at which tracer appears in muscle protein quantifies MPS rate; faster tracer incorporation indicates higher synthesis rates.

This approach permits measurement of "fractional synthesis rate"—the percentage of existing muscle protein replaced with newly synthesized protein per unit time (typically expressed as percent per hour). By comparing fractional synthesis rates across different meals or fasting periods, researchers assess how protein distribution affects synthesis responses.

Measurement of Amino Acid Metabolism

Beyond synthesis, research examining protein distribution often measures amino acid appearance and disappearance from circulation. When protein is consumed, proteolysis occurs in the gastrointestinal tract, releasing amino acids into circulation. Circulating amino acid concentrations reflect the balance between intestinal appearance (from dietary protein breakdown) and removal from circulation (into muscle tissue for protein synthesis or other tissues for alternative fates).

Tracer Kinetics Methodology

By providing labeled amino acids with meals, researchers measure the kinetics of amino acid appearance and removal. These measurements quantify: rate of amino acid absorption from the intestine (appearance rate), rate of amino acid uptake into muscle (disappearance rate), and fate of absorbed amino acids (incorporation into protein versus oxidation). This comprehensive assessment reveals not only synthesis rates but also the disposition of ingested amino acids.

Different distribution patterns produce distinctly different amino acid kinetic profiles. Even distribution produces multiple moderate peaks in circulating amino acids; skewed distribution produces fewer but higher peaks. These temporal profiles influence muscle amino acid uptake rates and contribute to different synthesis responses across distribution patterns.

Study Design Comparisons

Research comparing protein distribution patterns employs several distinct comparison frameworks:

Within-Participant Designs

Participants receive both distribution patterns in randomized order, separated by washout periods (typically 1-2 weeks). This crossover design employs each participant as their own control, reducing variance from inter-individual differences and increasing statistical power to detect distribution pattern effects. Crossover designs are particularly effective for acute studies of 1-3 day duration but become impractical for longer-term investigations.

Between-Participant Designs

Different participant groups receive different distribution patterns throughout the study. This approach is necessary for longer-duration studies but requires larger sample sizes to account for inter-individual variability. Randomization to distribution pattern minimizes systematic differences between groups.

Distribution Pattern Specifications

Studies typically define distribution patterns by meal number and protein quantity: "even" might specify three meals containing 25 grams protein each; "skewed" might specify two meals with 40 and 20 grams. Some studies examine continuous variables (e.g., meals ranging from 15-50 grams protein) rather than discrete categories. The specific patterns examined reflect study questions.

Participant Selection and Characteristics

Research on protein distribution varies substantially in participant populations studied. Understanding these differences is crucial for interpreting which findings apply to which populations:

Age Groups

Some studies exclusively examine young, healthy adults (18-35 years), effectively identifying mechanistic responses without age-related modifications. Others specifically recruit older adults (65-85 years) to characterize age-dependent differences. Studies including multiple age groups enable direct age comparisons. The population studied critically determines whether findings generalize to other ages.

Activity Status

Studies recruit participants with varied activity histories: some exclusively enroll sedentary individuals, others require recent resistance training participation. Activity status substantially modulates protein response; findings from highly trained participants do not necessarily generalize to sedentary populations and vice versa.

Health Status

Most research enrolls healthy individuals without chronic disease. Specialized studies examine protein metabolism in disease states (sarcopenia, diabetes, chronic kidney disease), revealing how disease modifies protein responses. When health characteristics differ substantially from study to study, findings may not be directly comparable.

Sex and Hormonal Status

Some research enrolls both males and females and examines whether sex differences exist in protein response patterns. Others preferentially enroll one sex. Hormonal status (menstrual cycle phase in women, testosterone status in men) can modulate protein responses; studies controlling these variables versus those not accounting for hormonal factors may produce different findings.

Nutritional Control and Confounding Variables

Controlled feeding studies attempt to isolate the effect of protein distribution while controlling other variables. However, no study can control all potential confounders. Key variables managed or uncontrolled in protein distribution research include:

Total Daily Calories

Most studies maintain equivalent total daily energy intake across distribution conditions while varying meal pattern. Some studies deliberately manipulate energy balance (surplus or deficit) while examining protein distribution effects. Energy balance substantially influences protein retention efficiency; studies with different energy balance approaches may produce different findings regarding distribution pattern effects.

Carbohydrate and Fat Composition

Macronutrient composition beyond protein influences amino acid oxidation and protein retention. High-carbohydrate, low-fat meals may produce different protein responses than other macronutrient combinations. Most studies maintain relatively constant carbohydrate and fat quantities across distribution conditions but rarely examine whether macronutrient combinations modify distribution pattern effects.

Protein Source Quality

Different protein sources—eggs, milk, beef, plant sources—contain varying quantities of essential amino acids and leucine. Studies typically use single protein sources (often milk protein or egg) to maintain consistent amino acid composition across meals. Findings from research using high-quality animal proteins may not generalize to plant-based protein sources.

Meal Timing and Spacing

The intervals between meals substantially influence results. Meals spaced 4-5 hours apart produce different patterns than meals separated by 2-3 hours or 8+ hours. Most studies specify consistent inter-meal intervals within each distribution condition but may vary intervals between conditions.

Statistical Approaches and Sample Size

Research examining protein distribution typically employs statistical tests comparing outcomes across distribution patterns. The choice of statistical approach, sample size, and data analysis framework substantially influences which effects appear statistically significant versus attributable to chance variation.

Sample Size Calculations

Properly designed studies perform a priori sample size calculations: determining how many participants are needed to statistically detect a clinically meaningful difference between distribution patterns, accounting for expected variability. Well-powered studies can reliably detect genuine distribution effects; underpowered studies may fail to detect real effects or may inappropriately conclude non-existent effects exist due to chance variation.

Acute studies examining immediate MPS responses typically require 10-20 participants per group to detect meaningful effects; longer-term studies examining cumulative adaptations may require larger samples. Variability between individuals in MPS response magnitude influences required sample sizes.

Outcomes and Interpretation

Protein distribution research measures multiple distinct outcomes, each providing different information:

Primary Outcomes

Muscle Protein Synthesis Rate represents the most commonly measured primary outcome, typically expressed as fractional synthesis rate (percent per hour). Circulating Amino Acid Concentrations and Plasma Leucine provide information about amino acid availability. Net Protein Balance combines synthesis and breakdown measurements to reflect net daily protein retention.

Secondary Outcomes

mTORC1 Phosphorylation and related signaling molecule activation reflect molecular mechanisms underlying protein response. Amino Acid Oxidation measures the fate of dietary amino acids. Hormonal Responses (insulin, growth hormone) reflect metabolic status.

Interpretation requires understanding which outcomes were measured, their reliability, and the study duration. Findings regarding acute MPS responses (hours) don't necessarily predict longer-term tissue protein retention (days-weeks). Mechanistic insights from pathway signaling studies don't necessarily translate to functional outcomes relevant to tissue health.

Limitations of Controlled Feeding Research

Despite rigorous methodologies, controlled feeding studies have important limitations:

Artificial Setting

Laboratory-controlled environments differ from real-world conditions in numerous ways: standardized meal composition, controlled activity, managed sleep, and absence of psychological and social influences on eating. Findings from highly controlled conditions may not precisely predict real-world outcomes.

Short Duration

Most protein distribution studies examine acute or very short-term responses (hours to days). Adaptation to chronic distribution patterns, effects on long-term tissue composition, and interaction with other lifestyle factors over months or years remain largely unexamined. Acute findings may not predict chronic effects.

Limited Population Diversity

Research often studies narrow demographic segments: university students or older adults within limited age ranges, predominantly one sex, specific ethnic backgrounds, and particular health/activity statuses. Findings from studied populations may not generalize to other demographic groups.

Publication Bias

Studies showing significant effects are more likely to be published than studies finding no effect. This publication bias means the literature may overrepresent findings supporting particular conclusions. Unpublished null findings remain unknown to readers.

Conclusion

Controlled feeding studies employing stable isotope tracers and precise measurement of protein metabolism have substantially advanced understanding of how dietary protein contributes to muscle tissue composition and maintenance. These methodologies enable measurement of previously immeasurable processes—synthesis rates, amino acid kinetics, and molecular signaling—providing mechanistic insights into protein physiology.

Interpreting research findings requires understanding study design, participant characteristics, measured outcomes, and duration. No single study definitively answers complex questions about optimal protein distribution; rather, research evidence accumulates across multiple studies employing diverse methodologies and populations. Considering the totality of evidence—which findings are consistent across studies and populations versus which findings appear idiosyncratic to specific conditions—permits balanced interpretation of protein distribution research.

Educational content only. This article presents scientific explanations without offering individual recommendations or guarantees regarding personal outcomes.

Back to research articles